Nowadays, all the craze in the enigmatic world of startups and innovative design seems to be about the Design Sprint. If you have worked on a design team of any type or have experience in contemporary product development, it is likely that you are already well acquainted with this process.

If you are unfamiliar with the Design Sprint process, then it’s about time you learn more about it to add an invaluable skill to your professional arsenal.

So, what actually is a Design Sprint.

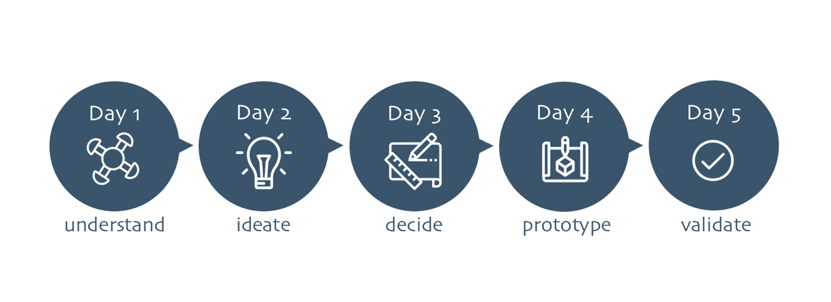

In short, a Design Sprint is a five-phase process to effectively answer business problems “through design, prototyping and testing ideas with customers”. This is according to the Google Ventures team who first refined and popularized the process a few years ago.

Please Note: It may provide some clarification knowing that: because of Google Ventures’ close ties with the Design Sprint process, they are commonly referred to as Google Design Sprints. We also refer to them in this post as “Sprints”.

The five phases are commonly broken apart to be completed on five subsequent days. In order, these phases are: understand, ideate, decide, prototype, then validate.

Like all Design Thinking processes, the power of the Design Sprint lays in placing those stakeholders who are affected by the problem at the center of the solution: customer-centric design.

The Specifics.

Even though the Design Sprint can and probably should be mastered by just about anyone, there is much more to know about the process than these five intuitive phases. This is because every “phase” in a Design Sprint is actually a methodology or process in itself that can be further broken down into additional processes (i.e. defined set of steps).

Below, each phase is briefly explored along with more details about when to use Design Sprints, Design Sprint planning, and overall execution.

When to Use Design Sprints.

Design Sprints are most commonly used as a tool to ideate solutions to a business’s customer-facing problems. For example, a household plumbing company may complete a Design Sprint to design an app that do-it-yourself customers can use to complete minor plumbing repairs.

Even though Design Sprints have been adopted as a way for startups to refine and validate their ideas before launch – and by product development teams to develop ideas for innovative products – its application extends much further.

Time and time again, Design Sprints have proved to be an invaluable process to find new marketing strategies, improved management practices, perfected workflows, sophisticated engineering solutions, etc.

Sprints help teams find stakeholder-validated solutions to problems before the commitment of resources. So, the Design Sprint can be used and, if necessary, modified to be a critical gizmo anytime there is a problem that effects multiple stakeholders.

Ultimately, determining whether or not the process should be used in a certain situation is circumstantial. As you learn more about the Design Sprint process by applying it in a number of different settings, you will get a knack for when it does and does not work best for your particular business.

Preparation.

Even though the Design Sprint, as Google Ventures uses it, is completed in just five days, it can take weeks of preparation to properly set the stage.

The Challenge

Before any thought is given to running a Sprint, there must be a clear problem that the business is facing. This problem that needs a solution is often times referred to as the “challenge”.

Jake Knapp, the Google Ventures partner who created the Design Sprint, lists three characteristics of a challenge where Design Sprints seem to shine brightest: high stake projects, challenges that are facing time constraints, and projects that are difficult to start and lack momentum.

However, as mentioned earlier, the Design Sprint is so versatile that is can be applied to nearly all situations.

Selecting the Design Sprint Team

The effectiveness of the Sprint is dependent on the cohesiveness of a diverse Design Sprint team. It is commonly recommended that the team is made up of five to seven individuals from the company with diverse skills and backgrounds.

Every Design Sprint must include at least one person from the organization who has authority to make decisions for the businesses, referred to as the “Decider”. The CEO or product manager may be an example of a Decider.

Another must-have role on the Sprint team is the Facilitator. This is the person who is in charge of the entire Design Sprint process. He or she must be comfortable running meetings and keeping the team moving in the right direction. The Facilitator should be different from the Decider.

It is also the duty of the Facilitator to gather the team and prepare the space. Additionally, he or she must schedule five stakeholders to be interviewed on Day 5.

Other team members include some mix of the following: a finance expert, marketing expert, customer (stakeholder) expert, tech expert, and a design expert. These are all individuals from the company who are acknowledged as specialists in their respective field.

It is worth noting that the customer expert has an important task to complete in the weeks prior to the Design Sprint. He or she must gather and understand stakeholder data (e.g. surveys, support tickets, customer interviews) that will be presented Day 1 of the Sprint.

Additional Things to Know

As Jake Knapp imagined it, Sprints occur Monday to Friday, starting at 10 a.m. and ending at 5 p.m. with an hour long lunch break right in the middle. Fridays have an extra hour, starting at 9 a.m.

The team should complete the sprint in a creative space with minimal distractions. For the most part, electronic devices are not permitted during Design Sprints. There should be whiteboards, post-its, markers pens, paper, snacks, and timers in the space.

Day 1: Understand.

On the first day of the Design Sprint, the team works to fully understand the challenge being explored. Before sharing viewpoints on the problem, the team must work together to explicitly define expectations and goals. A vision must be painted for the week. Furthermore, it should be clarified how this particular Design Sprint will fit into the broader strategy of the company.

After that, the challenge should be mapped. This means drawing a simple diagram displaying the steps that are taken by stakeholders as they move through the challenge. This diagram will help ensure the entire team is on the same page.

Next up is interviewing team experts. All experts will present their thoughts on the challenge before being questioned by the others. They should incorporate their insights on the challenge, focusing on pains related to their areas of expertise.

Often times, the most important expert to speak is the customer expert. This is especially the case for customer-facing challenges. The customer expert has constant interaction with customers (usually a central stakeholder) and is the team’s access into the mind of the target customer.

As experts are being interviewed, other team members should be taking notes on post-its, each idea on a separate post-it. Towards the end of Day 1, these sticky notes are to be hung on the wall. The team must vote on the ideas that they find most relevant to the challenge.

The ideas with the most votes will help the Decider, at the end of Day 1, choose the single most important step on the map that will be focused on throughout the rest of the Design Sprint.

Day 2: Ideate.

In his book about Design Sprints, Sprint, Jake Knapp states, “great innovation is built on existing ideas, repurposed with vision”. This is why the beginning of Day 2 starts with an overview of existing ideas and solutions that attempt to solve the challenge.

After existing ideas are briefly explored, the team will break apart to “sketch”. This is when team members draw upon notes from Day 1 to individually come up with ideas. These ideas are then sketched on paper. A sketch is commonly a set of diagrams or visuals explaining how the idea will solve the challenge.

Sketches should make even complicated ideas simple to understand without many words of explanation. Those who cannot draw will be happy to know that, as long as sketches contain solid critical thinking, the quality of the actual drawings does not matter.

Day 3: Decide.

Each team member should have a bunch of sketches drawn on paper by the end of Day 2. Day 3 will begin with all sketches being stuck onto walls for team members to silently examine.

Please Note: There are multiple other techniques used to vote on the sketches; however, we will explore just one of them here. Some of these include the heat map and straw poll.

As team members walk around the room analyzing ideas, they will each be given a certain number of votes represented by stickers or pen marks to place directly on sketches. After all votes are taken, the handful of sketches with the most votes will remain on the walls.

Sometimes, teams decide to review the remaining sketches and see if any ideas can be consolidated. If necessary, additional sketches may be added to the wall that embody characteristics from a number of promising sketches.

It is then time to once again use some sort of anonymous voting process to reduce the sketches down to one or two. This remaining idea(s) will be prototyped.

Before prototyping begins on Day 4, the team creates a storyboard for the prototype. This is a sequence of drawings that displays how the prototype will work and how stakeholders will interact with it. The storyboard can draw upon a number of aspects from other top ideas and not just winning ideas.

The storyboard is developed by the entire team. Contribution from all is important so that no individuals are left distressed the remaining two days. Also, making sure that all experts show interest and give feedback throughout the creation of the storyboard will increase the likelihood that the prototype is feasible and viable.

Day 4: Prototype.

The Design Sprint team has the next seven hours to build a realistic prototype that will soon be tested with stakeholders. The prototype should be of whatever quality that is possible for the team to build in the day.

Making the prototype functional is of little importance. As long as it properly exhibits the basics of the team’s original ideas while giving the impression that it is real, not else matters. This is because the entire goal of building the prototype is to get natural reactions from those stakeholders who will interact with it on Day 5.

So, if the prototype is capable of essentially tricking someone into thinking it is a real product, then the Design Sprint team has done its job. And I said “essentially” because it is many times unlikely that interviewees will literally think it is a real product. However, the prototype should feel so real that the interviewee momentarily forgets that it is just a prototype and interacts with it instinctively.

Various examples of Sprint prototypes include an interactive keynote that mimics a new iPhone app, someone pretending to be a medical scribe and handing out medical records for the interviewee patient to fill out, and an iPhone on speaker phone taped to a remote control mimicking a robotic receptionist.

The point is, the prototype will not be perfect and will take some creativity to construct. This can be fun for the team.

Day 5: Test.

Hopefully the Facilitator didn’t forget to schedule at least five stakeholder interviews on Day 5. This is where the magic happens.

One by one, stakeholders are brought in a space to be interviewed for roughly an hour. There should only be one interviewer, but the entire team will be watching the interview live via video while taking notes.

The interviewer will ask a series of open-ended questions to get a better understanding of the stakeholder’s background. The stakeholder will then be introduced to the prototype and given the opportunity to interact with it.

Once the interviews are done, the team will have many notes that will be openly shared. The group as a whole will organize these key insights on a whiteboard or on post-its stuck on the wall to be analyzed.

Altogether, these notes will spell out a rather consistent pattern, providing strong validation of certain aspects of the proposed solution as well as a number of clear criticisms. Like everything else throughout the week, it is critical to document what these are.

The end of Day 5 will be nearing. At this point, the team must explicitly state what they have learned over the past week and how that fits into the future of the business; the team will discuss what needs to happen next to accomplish the goals set on Day 1.

Moving Onwards.

The Design Sprint is complete. However, as mentioned before, action will have to be taken to accomplish the goals set on Day 1.

Momentum should always follow the Design Sprint. In some cases, the Decider will immediately push parts of the Sprint’s proposed solution to the product development team to begin its development. Other times, the team will choose to run a short workshop the following Monday to make a refined game plan. This can give team members time to reflect on the Design Sprint over the weekend.

Conclusion.

The beauty of the Design Sprint process is that no matter what, the team walks away with invaluable insights from the week. Validation is usually desired but, then again, stakeholder criticism can be just as helpful.

It is important to point out that this has been nothing more than an elementary overview of the Design Sprint process. To more thoroughly learn about Design Sprints, read Sprint. This book was written by Jake Knapp, the creator of the Design Sprint, and offers a comprehensive guide into how to complete the process. Also, we will be sharing a series of posts further exploring each day of the Design Sprint.

Pingback: Preparing For A Design Sprint - Educating Entrepreneurs