At Educating Entrepreneurs we firmly believe in the power of design thinking – and so do millions of individuals across the world. In fact, many of the world’s most innovative companies and inventors have made themselves masters in design thinking.

So, what is design thinking and why is it so useful.

Online, you will find countless definitions of design thinking. After reading four or five of these, things can get rather confusing. This is due to the abstract nature of design thinking.

Idris Mootee, the world-renown design thinking expert, describes it as “the search for a magical balance between business and art, structure and chaos, intuition and logic, concept and execution, playfulness and formality, and control and empowerment.”

The CEO of IDEO, Tim Brown, defines design thinking as being the “collaboration between creators and consumers”. This may be the simplest and truest definition of design thinking, although still rather abstract.

In more concrete terms, design thinking is a human-centered approach to problem solving. It is a proven iterative methodology to effectively design better solutions.

The reason design thinking is so effective is because it relies on human-centered data and feedback to inspire new ideas. This concept is relatively intuitive: to come up with a solution to a problem, you should first understand then develop a solution to that very problem while keeping in mind the needs of those stakeholders who are most strongly effected by it.

Ultimately, by drawing upon the experiences and reactions of relevant stakeholders, you are able to create and validate your ideas through the judgment of relevant stakeholders, increasing the likelihood of successfully solving the problem at hand.

This means that a specific problem (known as the challenge), can be solved with more accuracy, reducing the inherent risks in successfully bringing products to development and policies to the implementation stage. Reducing the “inherent risks” means saving time, money and other resources.

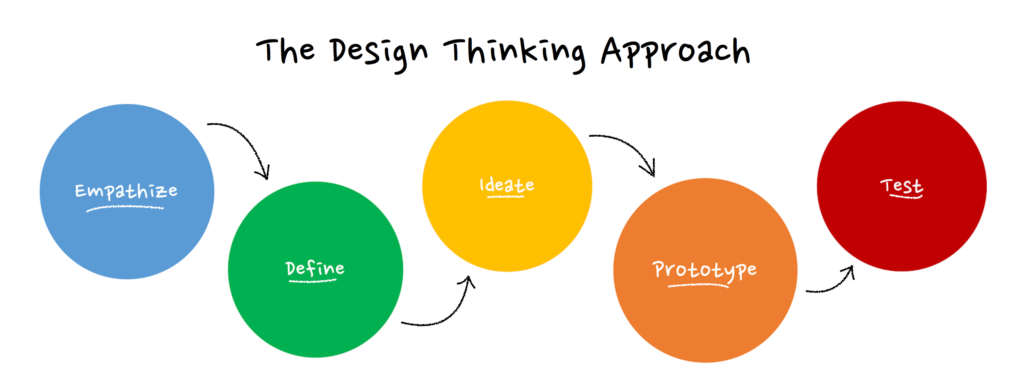

The design thinking approach is easiest to understand when broken down into five stages: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. Below, find a stage-by-stage overview that you can implement into your own startup.

(1) Empathize.

Once a problem is identified, the very first stage is to empathize with the stakeholders. As mentioned earlier, understanding those who are affected by the problem must be placed at the center of the designer’s consideration.

In many instances, stakeholders primarily consist of consumers from the company’s target market. However, when the design sprint is used as an approach to solve a more complex, internal facing matter, stakeholders will include those within the organization.

Generally, as long as the designer is able to feel true empathy for the problems that others are feeling, this stage can take multiple forms. Many times, the designer will hold individual meetings with stakeholders. These meetings are referred to as empathy interviews. Empathy interviews attempt to evoke raw, unfiltered emotions from the interviewee by asking a number of open-ended questions.

Alternatives to empathy interviews include shadowing, where stakeholders are observed interacting with certain dimensions of the problem. Regardless of which methods are used in this stage, it is important that the designer remains non-judgmental and unbiased while seeking to understand the needs and emotions of identified stakeholders.

(2) Define.

The second stage of design thinking is to transform whatever was learned from the empathize stage into insights. The identification of challenges, needs, pain points, and the development of a persona are all common practices in this stage.

At the very least, the designer must explicitly note stakeholders’ largest pain points in response to the problem. These are often times highlighted by non-verbal cues observed in Stage 1.

The development of a persona is a very effective tool to consolidate pain points and other insights established from the empathize stage. As Ironside notes, “A persona is not based on any specific person, but is an abstract representation of many people with similar characteristics.”

Creating a persona for a large number of stakeholders observed in the empathy stage can help the designer remain focused on stakeholders’ most pressing matters without getting distracted by all of the extra clatter that was witnessed in the process. For those familiar with marketing, the persona(s) is the design sprint equivalent to the development of the target market profile(s).

(3) Ideate.

Once the designer becomes fully capable of defining the problem from the standpoint of the stakeholders, she is ready to ideate. Design thinking methodology does not necessarily determine which specific techniques of ideation should be used, but does advocate some form of divergent and convergent thinking.

Divergent thinking is all about generating lots of ideas – brainstorming. As two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling once said, “To have a good idea, you must first have lots of ideas.” Most experienced designers would agree with Pauling as, early on in the Ideate Stage, they have learned to value quantity over quality.

The reason why quantity is often times more important than quality is because as a design thinker hurriedly searches her mind for more ideas to solve the challenge, she subconsciously draws upon her creativity as well as observations she made in Stage 1.

Once a series of brainstorming techniques are used, the designer uses convergent thinking to eliminate a large number of the ideas generated earlier. For obvious reasons, this elimination process can be extremely difficult for those new to design thinking.

To help make the designer’s decision easier, she should reject those ideas that do not coincide with the insights developed in Stage 2. If an idea seems to do a poor job of satisfying the pain points of the designer’s persona, then the idea should be abandoned. Those ideas that are not feasible nor viable should also be left behind.

An iterative process of divergent and convergent thinking is often used until there are three or less ideas remaining in the designer’s opportunity set. Whatever ideas are left at the end of Stage 3, the designer will prototype in the following stage.

(4) Prototype.

This stage is where the design thinker unleashes the power of the prototype to turn his top idea(s) into a more tangible model to be tested later in Stage 5. Glen, Suciu, Baughn and Anson provide a perfect summarization of prototyping in their scholarly article on design thinking:

“The point of prototyping in design thinking is to generate many iterative, throwaway prototypes with the minimum fidelity needed to gain critical feedback from the customer.”

Because design thinking is such an iterative approach, it is critical for designers to remember that initial prototypes can lack both physicality and complexity. (Side Note: For those who are familiar with prototyping design flow and its jargon, initial prototypes in the design thinking approach are not technically “prototypes”; they are usually sketches, wireframes or mockups. However, for the sake of simplicity, all models in this stage will be referred to as prototypes.)

A prototype with minimum fidelity is often times recommended due to its many benefits. Some of these benefits include fewer misused resources (time, supplies, etc.), greater creativity out of the design thinker, and a more basic, succinct model to show stakeholders in Stage 5.

So, what are some examples of prototypes with the “minimum fidelity needed”? If a designer is developing a prototype for a new financial management mobile app, he can quickly piece slides together on PowerPoint instead of creating a functioning app. Even less, he can simply sketch the app out in his notepad.

On the other hand, if a physical product is being prototyped, then the designer may decide to use glue and simple office supplies to build the early prototypes instead of a 3D printer. Other tools used during this stage of the design thinking approach include storyboards and acted out scripts. The point is, as long as this prototype is able to present the essence of the original idea, then it will suffice.

(5) Test.

In the Test Stage, the designer once again reaches out to stakeholders for feedback to provide immediate insights. This time, however, the designer is sharing her prototype(s) with stakeholders in order to seek approval and disapproval about the effectiveness of such a prototype.

Methods of getting feedback from stakeholders include role playing and individual interviews where stakeholders can freely interact with the prototype. It is crucial for the designer, yet extremely difficult, to not influence the opinions and behaviors of stakeholders during such interviews.

The ultimate goal of this stage is to understand what does and does not work with the current prototype and why. Are the pain points of stakeholders fully addressed? Is there strong validation about any certain features of the prototype?

After observing a number of stakeholders’ interactions with her prototype, the design thinker will eventually be able to confidently answer the questions above. At this point, she will likely choose to revisit Stage 4 to enhance the prototype, only to return to Stage 5 to seek additional validation and disapproval of the latest prototype.

After repeating this back and forth approach of prototyping then testing numerous times, there will come a time when the designer finds enough validation to confidently bring the improved prototype to the next phase. Whatever is next, design thinking does not dictate. The methodology is complete. The designer may choose to craft a much higher fidelity prototype or bring her insights to the development team, using Lean Startup to build a Minimal Viable Product (MVP).

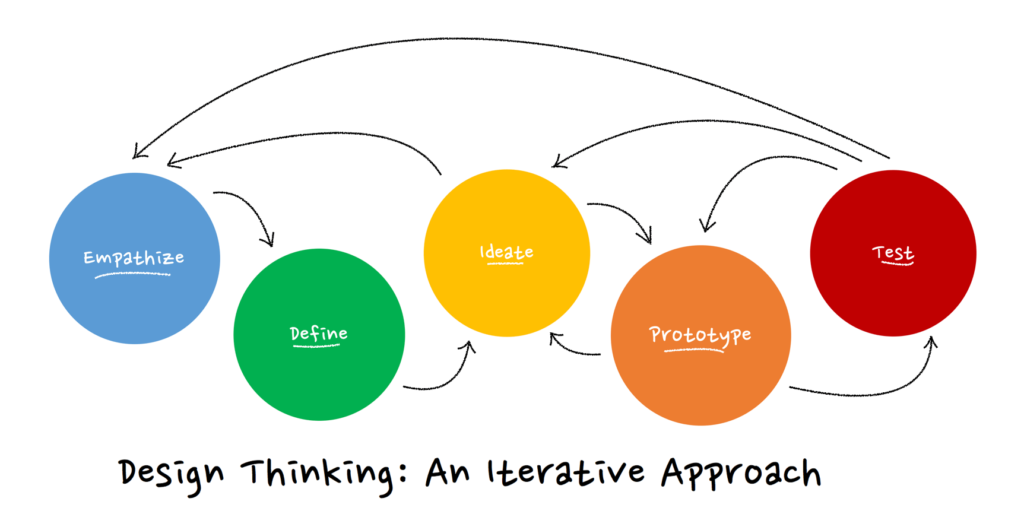

An Iterative Approach.

You have likely noticed that the word “iterative” has been used several times throughout this post. This is for good reason. Design thinking is a fundamentally iterative approach, meaning it involves iterations.

For example, in the Define Stage, the design thinker may return to the Empathize Stage to better understand a specific pain point that was initially overlooked. Or, after completing the Test Stage, the designer may fall upon responses that will cause the actual problem to be redefined in the Define Stage.

Another common occurrence is that findings from creating and testing the prototype in the Prototype and Test Stages will act as a catalyst for improved ideation. In this case, the Ideate Stage will be revisited to generate additional ideas before going through the remaining stages once more.

The important thing is to remember that design thinking, like all effective design, is never a linear approach. Because of this, design thinking may seem chaotic to those first attempting to use the methodology. As with most things, practice makes perfect, and design thinking is no exception.

A Group Approach.

Is the design thinking approach most effective with just one designer or many designers? This is a whole other topic in itself that will be explored in a future post. Depending on the nature of the problem being explored, the size of the design team will vary.

For now, know that a small group with team members that have a variety of backgrounds and disciplines is typically advantageous.

So, can I become a design thinker.

If you work at an imaginative company anywhere near Silicon Valley, such as Google or IDEO, you are already very familiar with design thinking. This is also probably the case if you are getting your B.S. in entrepreneurship or are enrolled in some other program that mixes creativity with business.

For the rest of us, design thinking may be a mystery or, if not a mystery, may seem like a scary thing: an apparatus useful for only engineers and professional designers. However, this is a delusion. Everyone is capable of becoming a design thinker.

If used properly, design thinking can help an individual come up with innovative solutions to real-world problems, no matter his or her age or profession. Furthermore, through experience, it has been realized that design thinking is a valuable approach to innovative design no matter the field to which it is applied.

It can be just as valuable to a college entrepreneurship student brainstorming her next big idea as it is to a pharmaceutical company attempting to fix a bottleneck in its drug development process.

Because of its versatility, effectiveness and simplicity, it makes a lot of sense for you and probably everyone you know to become a design thinker.

Conclusion.

Even though design thinking is unpretentious and fairly self-explanatory (empathize, define, ideate, prototype, then test), there is a lot more to learn to fully understand the beauty of this design approach. In reality, this post is nothing but an elementary overview of what it entails.

If you feel motivated to become a master of design thinking – which would certainly be handy to you in the future – we recommend you start by reading Change by Design by Tim Brown. Also, check back with us as our future posts will break down design thinking in more detail.

Pingback: Design Thinking, Design Sprint, Lean Startup, and Agile: How do they come together? - Educating Entrepreneurs

Pingback: Entrepreneur's Are Defined By Critical Thinking - Educating Entrepreneurs